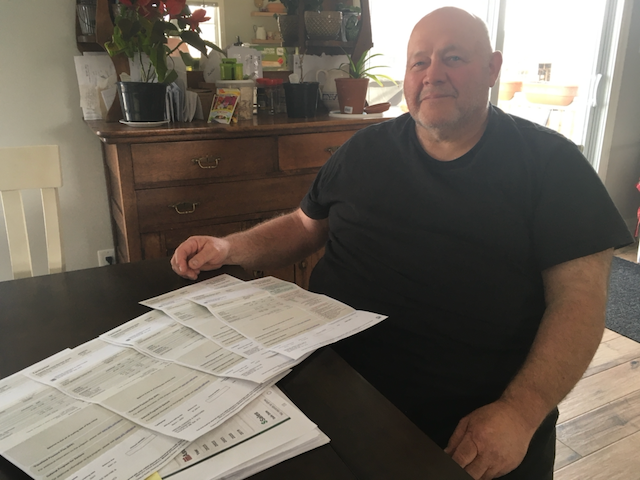

When Terry Greene opened his tax bill this year, he was disappointed, but not surprised. Greene knew his assessment was hiked again for the third year in a row, but he had expected something else to change: his tax rate.

Greene lives on Queens Road in Frosty Hollow, on the outskirts of the former town of Sackville, and now part of Ward 2 in the town of Tantramar. “We knew what our assessment was going to be,” says Greene. “But we were under the assumption that because we voted in Ward 2, and we were divided off into Ward 2 of the Tantramar region, we expected our tax bill to be as an LSD [Local Service District] of Ward 2.”

“We got our tax bill and our tax bill still has us as part of Ward 3, which is not an LSD, it’s a fully serviced district,” says Greene. “And the tax rate difference is 40-some percent… And I don’t feel that’s right.”

Greene says his property became part of the town of Sackville in the mid 70’s, during an expansion of the town boundaries. Since he can remember, he’s been paying town of Sackville tax rates, but Greene feels the level of service he receives in Frosty Hollow is closer to what is available in the former local service districts just down the road from him, where property owners pay much less in property tax.

When his house was built, another property owner built a similar house down the road, says Greene, “maybe one kilometre from here, maybe not quite.” That house is assessed at a similar value to Greene’s, but the owner pays a much lower tax rate. “His tax bill is $4,000,” says Greene. “I’ll trade him houses, you know, he’s got equal house.”

Greene’s tax bill this year is just about $7400, up from $6500 two years ago, and just $3900 four years ago. That’s all been at the same tax rate, if you don’t count the one cent cut that former town of Sackville taxpayers saw this year.

The Greenes saw a massive spike in their assessment in 2021 after they rebuilt their house due to a fire. But since that initial rebuild assessment of $409,000, Service New Brunswick has increased their assessment another nearly 20%, to nearly $494,000.

The one time Greene called Service New Brunswick to enquire about an appeal, he was told he had better not, because his assessment could actually go even higher. So Greene decided not to proceed with an appeal.

But it’s actually Greene’s tax rate that bothers him the most these days, because of how it seems disassociated from the services he receives, and also because of a new electoral ward map issued by the department of local government. The ward map for Tantramar appears to follow the line between areas that have water and sewer service and those that don’t, and Greene’s property lies squarely in the latter, inside Ward 2, with the rest of the former Sackville Local Service District (LSD). That’s why Greene expected to see a different tax rate on his bill this year.

But the map of Ward 2 (and all the other wards used to elect 8 Tantramar councillors last November) has nothing to do with taxes, say Tantramar CAO Jennifer Borne and acting treasurer Michael Beal.

“Taxing authorities and ward boundaries are two separate things,” says Borne. “Ward boundaries, are for electoral purposes only. The main message is taxing authority remains the same as what you were pre-amalgamation.”

The decision on boundaries for the wards had to do with distributing the population relatively equally, to ensure fair representation, says Beal. “It’s not perfect because of the layout of the land, but they tried to get the ward voting populations as close as possible.” (They didn’t quite succeed in that goal, with the number of voters per councillor in the surrounding rural wards nearly half of the number in the central Sackville ward.)

The separation between electoral ward boundaries and tax authority boundaries was also confirmed by department of local government spokesperson Vicky Lutes, who wrote in a email to CHMA that, “tax rates are not created based on wards, but on taxing authorities.”

“That’s where the confusion I think may have come into play,” says Beal, with people thinking because their voting situation changed, so should their taxing situation. “No, your voting situation changed but your taxing authority remained the same as it was,”

The same discrepancies in tax rates occur elsewhere in Tantramar. Ward 1 actually includes three different taxing authorities: the former village of Dorchester, the former Dorchester LSD, and the former Sackville LSD, each with their own different tax rate this year, set by the province.

And while the boundary for Ward 3, central Sackville, appears to follow the water service boundary in places, Beal points out that there are still parts of Ward 3 without water service, such as parts of Walker Road.

Ratepayers versus taxpayers

The division between areas with water and sewer services and those managing their own wells and septic systems has long been contentious around tax time, but according to Beal and Borne, there is actually no relation between the tax rate charged on a property and the water or sewer services it receives.

“They’re two separate budgets,” says Borne. “Anyone that would be unserviced is not paying for the utility service.” Borne says the roughly $2.5 million utility budget for Tantramar is actually managed by two sub-budgets, for the service areas in Dorchester and Sackville.

Beal says that aside from an amount the town pays to the water utility to cover hydrant costs (just under $400,000), water and sewer utilities are fully funded by ratepayers, who in Sackville get four bills per year totalling a minimum of $540, plus metered charges over that minimum. Dorchester ratepayers pay a flat fee of $715 per year.

In reality, those amounts don’t quite raise enough revenue to properly take care of the sewer and water infrastructure, says Beal. “We’re only currently funding about 20% to 30% of our utility infrastructure needs on an annual basis,” says the acting treasurer. That doesn’t just include the town’s sewage lagoons, but also the ageing pipes and other infrastructure underground. Regular water main breaks are now de rigueur for Sackville, but spending on replacing them remains unattractive politically.

“Nobody wants to pay more water and sewer fees,” says Beal. “Nobody wants to pay more in any charges. But we’re trying to get to the point where we can fund more utility upgrades and minimize the additional cost to the ratepayers.”

For a few years now, the town of Sackville has been slowly ramping up bills by increments of $20, in order to sock away money to eventually upgrade the utility’s sewage lagoons, and maintain water and sewer mains. The concept is to have the money in hand, and prevent having to borrow, with the additional cost that comes with it.

Underfunding of infrastructure aside, the point Beal and Borne make it that the provision of water and sewer services is covered by ratepayers, and the rest of the town’s services are covered by taxpayers.

But that separation doesn’t jive with what was promised in 1974, when Sackville grew to encompass Frosty Hollow and other rural areas. Back then, recalls Greene, the plan was to extend water services to the entire town.

Beal recalls hearing the same thing from former staff and councillors, though it dates back to before his time with the town. But, he says, talk about the expansion of water and sewer utility service has focussed on its feasibility. “Every discussion that we’ve had around a table is that we don’t have enough money to fund our current infrastructure deficit, how can we expand the boundaries? Unless the provincial or federal government are going to come on board.”

Greene himself has long since given up the idea that water services will come out to his property in Frosty Hollow. But beyond water and sewer, he also finds other services lacking. He contributes to fire protection as part of his town taxes, but only has a dry hydrant near his house, which wasn’t working during the fire that destroyed his previous home in 2020. The fire department had to come in with water tanker trucks instead to fight the blaze, and Greene has concerns that more of his house could have been saved with a functioning hydrant.

There’s also no sidewalks or safe place to walk along his road, and no streetlights.

“We’ve been buying VIP tickets for 46 years,” says Greene, referring to his town of Sackville tax rate, “and the beer cart doesn’t go by here and there’s no porta-potties. It’s as simple as that.”

A matter of fairness

Greene’s issue with his tax rate really comes down to a question of fairness. Greene feels he should have the same tax rate as his neighbouring local service district, which this year is about 40% lower than the former town of Sackville rate.

At the same time the former LSDs are on track to see their tax rates go up significantly over the next five years, to bring them more closely in line with what the town and village have been paying. And the conversation about fairness will only get more complicated as LSD tax rates continue to increase.

Some of the concerns that may come from LSD residents concerned about rate hikes could stem from the way electoral reform has been framed by politicians like local government minister Daniel Allain.

“I think there are some people living in local service districts who maybe follow the municipal reform project and said gee, I thought Minister Daniel Allain said that we shouldn’t really expect our taxes to go up unless our services improved,” says politics professor and former Sackville town councillor Geoff Martin. “Well, I think he said that knowing that wasn’t really the case.”

“This is where I think you get into politics and questions of honesty and openness and so on,” says Martin. “The rates are going up in rural New Brunswick, not because they’re getting more services, but because the municipalities have believed for a long time—20, 25 and 30 years—that other things being equal, those rates should go up, because people living in the local service districts are benefiting from services provided for by the former towns or villages.”

In Tantramar, Martin lists examples like access to parks and playgrounds such as Lillas Fawcett and Beech Hill, sidewalks and a retail zone downtown, and subsidized events such as fairs, parades, and fireworks. All those things have been paid for by the town and villages, and not by surrounding local service districts. The Tantramar Civic Centre is another example. The widely used ice rink is a big ticket item for Sackville’s recreation budget, to date solely paid for and operated with tax payments from inside the former town of Sackville boundary.

The Tantramar budget presented by the province in January promises to change that, with a five year plan to move all tax rates closer together. The goal is to take the cost of shared services, such finance and administration, fire services, parks and recreation facilities, and tourism and recreation programming, and share them equally, eventually. But costs for transportation and policing services, two of the costliest items for municipalities, will remain separate and unshared.

“They’re indicating that there will be a correction over the next five years,” says Greene. He says that won’t affect his case that he should be paying a local service district rate. He also warns that the adjustment upwards in taxes is going to be “catastrophic” for some of his LSD neighbours.

“I’m angry,” says Greene. “They’re going to be a lot angrier… People down there, they won’t afford to keep their homes.”

Martin sees the same concern on the horizon, especially considering the economic climate of skyrocketing property assessments and daily living costs. “I’ve kind of been expecting a bit of a revolt, actually, as people got tax bills in March,” say Martin. “And in some ways, I’m a little surprised we’re not hearing more about it.”

What can council do?

The questions that are arising about fairness: Are property owners in rural and town areas sharing the right costs? Are the taxing authority maps drawn to accurately reflect rural and town areas? And are the tax rates justifiable in general? Those are questions that Beal and Borne say belong with elected officials.

CHMA reached out to councillors from all the wards which include former local service districts to ask what they had been hearing from constituents. We did not hear back from Debbie Wiggins-Colwell in Ward 1, Barry Hicks in Ward 2, or Matt Estabrooks in Ward 4.

Greg Martin in Ward 5 was the only one to respond to CHMA’s email, but he declined an interview on the topic. Martin said he had heard very little from constituents on tax bills, and also felt he needed to learn more about how the system works before weighing in.

Tax authority boundary changes on the horizon?

While the setting of tax rates is officially part of council’s purview starting in 2024, the setting of tax authority boundaries is not so clear. The department of local government refused CHMA’s interview request with deputy minister Ryan Donaghy on the topic, instead sending a brief email statement which did not answer a question about whether or not Tantramar council would be able to redraw tax authority boundaries.

Jennifer Borne thinks at the very least such a change would involve the cooperation of the province.

“It’s certainly something that [council] could take to the province and say, hey, we would prefer if you look at this model, based on what our residents are telling us,” says Borne.

Beal agrees that the final say on the taxing authority maps lies with the province, as there are no municipal bylaws outlining the boundaries of taxing authorities. But he says Tantramar council could certainly recommend making changes, and will have to eventually, as the five year plan to converge tax rates progresses.

“The idea with the province, from my understanding, was that you now have five taxing authorities, don’t go to 10 taxing authorities. Try to go down to two or three taxing authorities in the future. But you can’t do that until you get through the transition process,” says Beal.

As for Greene, he is hoping that Tantramar council will consider changes before the five year transition is up, because the taxes he is now paying could make his home unaffordable for a retired couple in the long run.

The Greenes say they will be presenting to Tantramar council at their next regular meeting on April 11. According to Tantramar’s new procedures, the time for public presentations will be limited to just five minutes, plus question and answer time from councillors.

The Greenes are hoping to speak with others in Tantramar who are facing similar situations and have set up a Facebook page as a gathering point, called Over taxed and unserviced in Tantramar.