It’s been just over a year since veteran journalist Bruce Wark published the first in a series of articles looking at allegations of harassment and bullying in the Sackville Fire Department.

Wark spoke with a number of current and former firefighters, who told him that although they had brought their concerns to the town’s senior management, they went nowhere and no actions were taken to address them.

Since then, the town of Sackville has taken some actions. At the end of April 2021, the town announced it was hiring Montana Consulting to do “a comprehensive workplace assessment of the Sackville Fire Department and its operations.” At the same time it noted that changes would be coming to the bylaw governing the fire department.

In September 2021, Montana handed over their report—containing 20 recommended actions—to town of Sackville CAO Jamie Burke. Montana also presented on their findings and recommendations to Sackville council and firefighters, and town staff say that work on implementing the recommendations is ongoing.

What are those 20 recommendations, and what’s inside the report and presentations discussing them? All of that remains confidential.

That bothers Bruce Wark, a longtime journalist (and occasional contributor to CHMA’s Tantramar Report), former journalism professor, and Sackville resident. Shortly after the town announced the Montana report was complete, Wark sent a request under the New Brunswick Right to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (RTIPPA) to the town’s clerk, Donna Beal, asking for access to the report.

Twenty-nine days later (just a day short of the allowable timelines under RTIPPA) Beal denied the request, citing section 20 of the act, which excludes the substance of personnel or harassment investigations. But Wark says the Montana report is more than just a personnel investigation. “When the town announced that it was commissioning Montana consulting to do that report, it called it a comprehensive workplace assessment,” says Wark, “and said that the town was committed to revising the bylaw governing the fire department.” With the scope of Montana’s work going beyond a simple harassment complaint, Wark argues that what Montana had to say about fixing the department should be open to public scrutiny.

“I felt I should get the whole report and should be able to judge for myself, or any member of the public, whether there was an independent, impartial and thorough examination of these charges,” says Wark.

So Wark took his argument to the next level, and filed a complaint with the provincial Ombud’s office. After a back and forth with an investigator, Wark got his final decision from Ombud Marie-France Pelletier on April 22. She supported the town’s position to withhold the entire Montana report, and refused to investigate the matter further.

That means that short of someone taking the town to court, the report, and its 20 recommendations to improve the working conditions of the Sackville Fire Department, will remain protected from public view. Wark says the decision will impact his future coverage, as the town looks at ways to rectify the problems he helped expose.

At an April council meeting, CAO Jamie Burke told council that revisions to the fire department bylaws would be a fundamental part of improvements to come, and the town’s legal team would soon be ready to bring those changes to council and the fire service.

“We can’t measure [the town’s reforms] against the report, which was supposed to be independent, impartial and a thorough investigation,” says Wark. “So we’re kind of blinded there. And it doesn’t help that the town council itself, the councillors who could be demanding more information, are not doing it.”

Wark points out that the decision to keep the report confidential not only freezes out members of the public, but also to a lesser extent the councillors who have seen a presentation from Montana discussing the findings of the report, but not the report itself.

“Not only is it hard for journalists or members of the public to ask questions about what is or is not happening with the fire department, the councillors themselves aren’t in much of a position either, because they’re not seeing the full report,” says Wark. “As long as this stays in place the way it is, I think that it’s going to be harder to cover what reforms are being made and whether they’re effective or not.”

Balancing privacy and right to information

Wark points out that he had always expected privacy concerns to affect what was released, as is often the practice when public bodies answer freedom of information requests. “I’ve never argued that if there are specific names and privacy concerns within the report, that that should not be redacted before it’s released publicly,” says Wark. “That’s the way it works with freedom of information generally.”

“When someone applies for a report in any other jurisdiction other than New Brunswick,” says Wark, “they look at the full thing. They decide, well, there are some things in here that we can’t release publicly, so they redact them, and then they release the rest. Here, the claim is that the whole report – every single word and comma and exclamation mark – has to be kept private.… I think it’s insupportable.”

Wark says the principle of access to information, or the public’s right to information, is that “the maximum allowable” amount of information should be released, with carefully defined exceptions. But in the case of the Montana report, he sees the exceptions being applied with a “broad brush,” locking up the full report because it deals with a personnel investigation. “I don’t think that that would fly in Nova Scotia,” says Wark, “or Ontario or anywhere else I’ve worked. I just think this is a peculiar thing in New Brunswick.”

New Brunswick tied for last in Right to Information

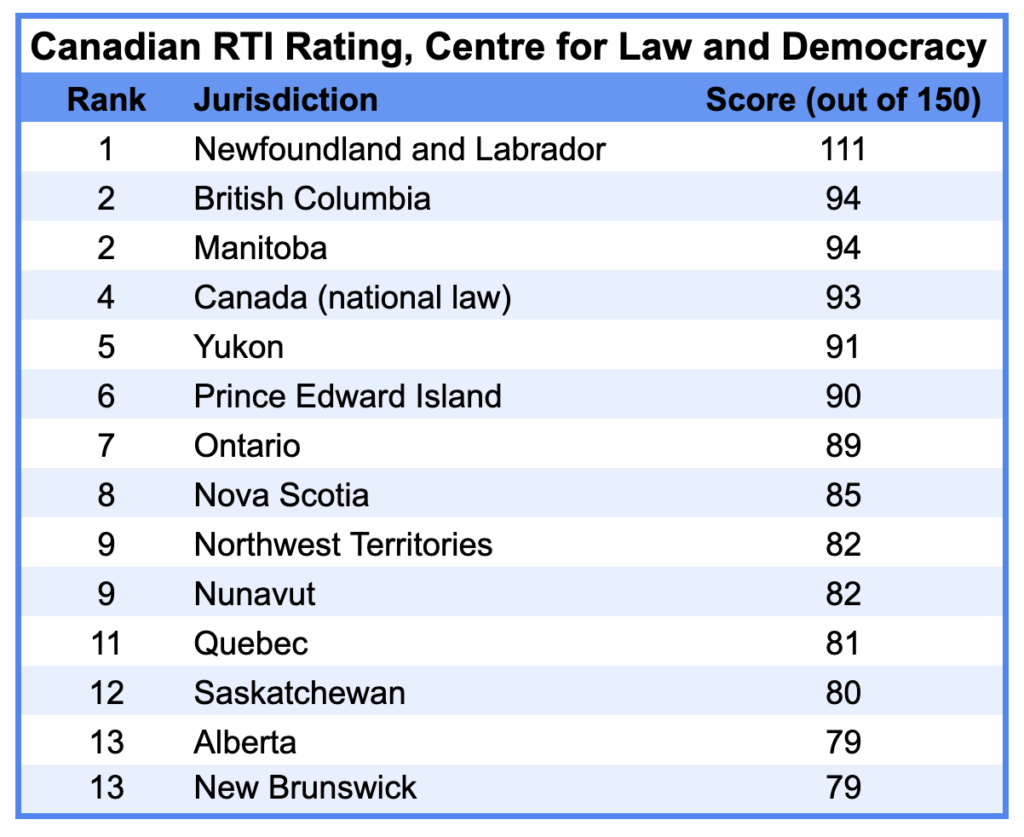

New Brunswick is indeed at the bottom of the barrel when it comes to access to information in Canada. The province’s RTIPPA ties for last place alongside Alberta’s access to information law on the RTI Rating, a global index developed by the Centre for Law and Democracy, which measures the strength of legal frameworks for public access to information.

And being last in Canada is even slightly worse when considering Canada’s position on the global RTI ranking is 52 out of 136 countries.

“The fundamentals are wrong in New Brunswick,” says Toby Mendel, executive director of the Centre of Law and Democracy, “worse than anywhere in Canada. And that’s within a framework of fairly poor performance as compared to the rest of the world, essentially.”

Mendel says he cannot speak to how the law is implemented in New Brunswick, just to the basics of the law itself. “A weak law will have overbroad, vague exceptions so people who are minded to be obstructive can rely on them to refuse access,” says Mendel.

But it’s not just a matter of weak laws. There’s also how the law is overseen, and Mendel points out at least one peculiarity with how Wark’s complaint was handled.

Wark originally dealt with an investigator from the Ombud’s office, who backed the town’s position, citing a previous decision in which citizens in Tracadie were also denied access to a workplace assessment of their fire department. After Wark pursued his complaint, the investigator doubled down, citing another section of the RTIPPA that allows for the protection of “advice, opinions, proposals or recommendations developed by or for a public body.”

That reaction from the Ombud’s office caught Mendel’s attention. “The purpose of the Ombud is to review the decision of the town, or the decision of the original decision maker, not to go through and see if there are additional reasons to refuse to give access,” he says. “If the town didn’t raise an exception, I don’t really see why the Ombud should be doing that. So I thought that was peculiar, and doesn’t give me a great sense that this person wishes to strongly promote access to information.”

“One of the hallmarks, as we have experienced it around the world,” says Mendel, “between a well functioning and a poorly functioning system, apart from the quality of the law and a few other factors, is the strength of the oversight system. Where you have a strong, active, engaged oversight body —whether that’s an information commission, and information commissioner, or an ombudsman — that tends to promote much better implementation.”

Wark says he sees a need for a dedicated office to oversee New Brunswick’s RTIPPA laws, as there was in the province before 2017, when then-commissioner Anne Bertrand retired, and her job was rolled into that of a new Integrity Commissioner. It has since been assigned to the office of the provincial Ombud.

“Maybe I’m bitter, but I’m not sure there’s the expertise in the Ombud’s office that you would have in a dedicated Access to Information Commissioner,” says Wark, “because this is just one thing on their plate.”

Fire department ‘still in crisis’

Despite not having access to the Montana Report, Wark is continuing to cover what’s happening at the fire department.

“There are still sources of information about what is or is not happening in the department. And that’s about all you can do,” says Wark. “You can also raise questions at council meetings. And I think firefighters themselves might raise questions.”

Wark notes that firefighter Travis Thurston was present at the last council meeting on April 11, and asked about the tracking or reporting of the department’s response times and attendance. Deputy Mayor Andrew Black, who serves as the liaison councillor for public safety, told Thurston that he could not recall response times and attendance numbers included in monthly departmental reports from Chief Craig Bowser.

“Judging by what I’m hearing,” says Wark, “the fire department is still in crisis.” Wark says he’s been told that the department is short-staffed and experiencing longer response times as a result of low morale. And so year after breaking the story, Wark will be continuing his coverage of issues in the department.

“It’s something that won’t necessarily go away,” says Wark, “because it’s too important a thing to let drop.”

Listen to the full interview with Bruce Wark here:

And listen to the full interview with Toby Mendel here: