An environmental group has launched two online maps showing areas of forest that have been sprayed with herbicide or approved for herbicide treatment, including some sections of protected watersheds.

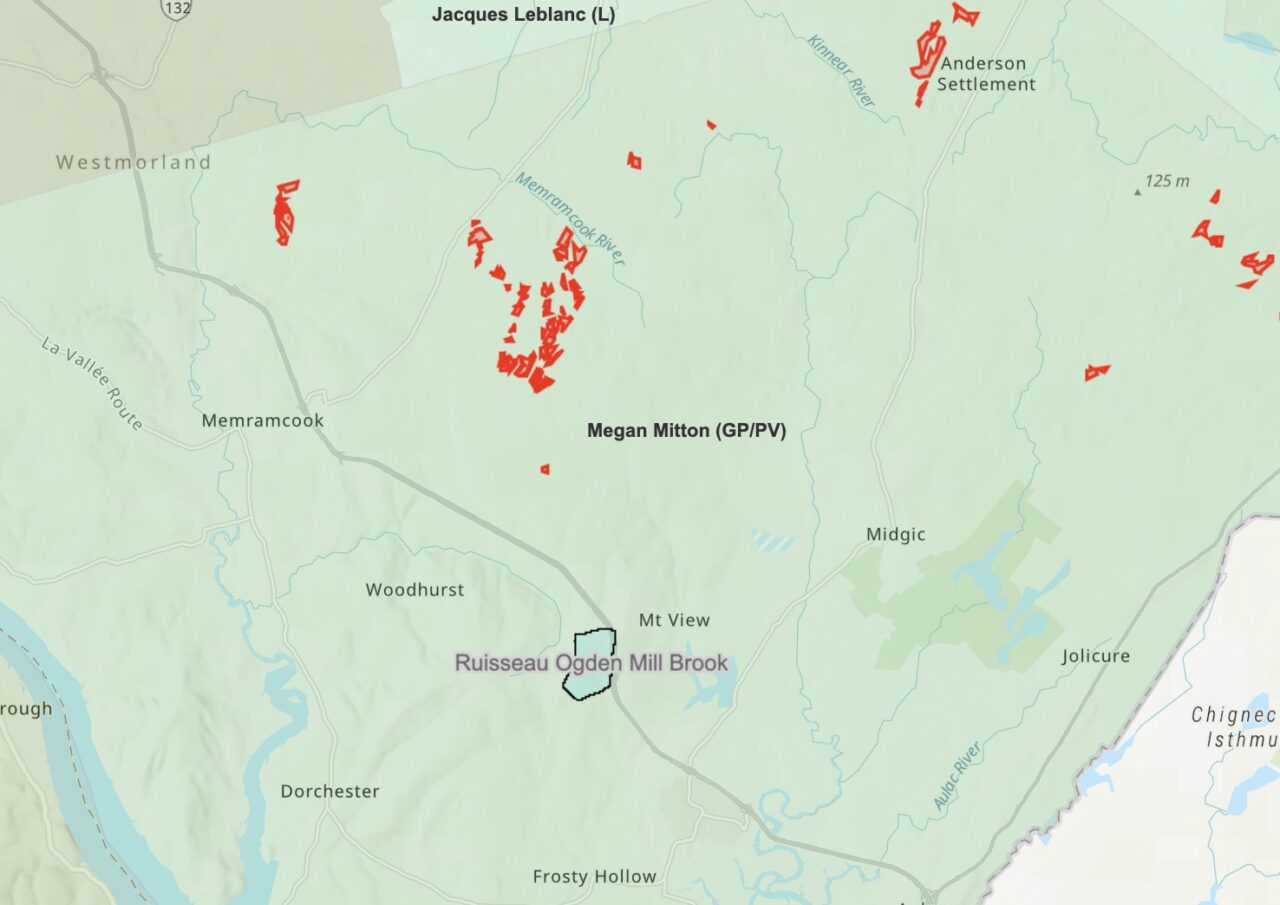

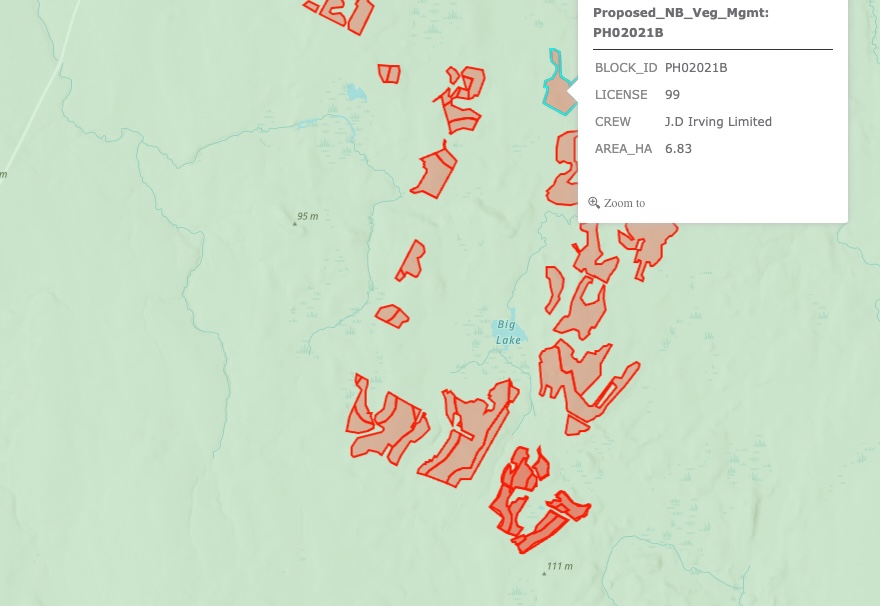

Sackville’s drinking water supply wasn’t directly targeted for herbicide spraying, at least last year, but the provincial government approved herbicide spraying by forestry giant J.D. Irving Limited on land a few kilometres north of that area, according to one map.

A volunteer from Stop Spraying New Brunswick pieced together the maps using publicly-available data from the provincial government. The group says the government should do a better job of making the information available, and the responsibility shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of a volunteer-run organization.

“If protected areas are being sprayed, I think the public has a right to know,” said Caroline Lubbe-D’Arcy, the group’s chair. CHMA has reached out to the Department of Environment and Climate Change for comment.

Listen to the interview with Caroline Lubbe-D’Arcy:

One of the maps shows areas of Crown land that have been treated with herbicide from 1969 up to the present date. Private land isn’t included because that data simply isn’t available, according to Lubbe-D’Arcy.

A second map shows areas of land where the government approved spray licenses during the 2022 spray season for both public and private forests.

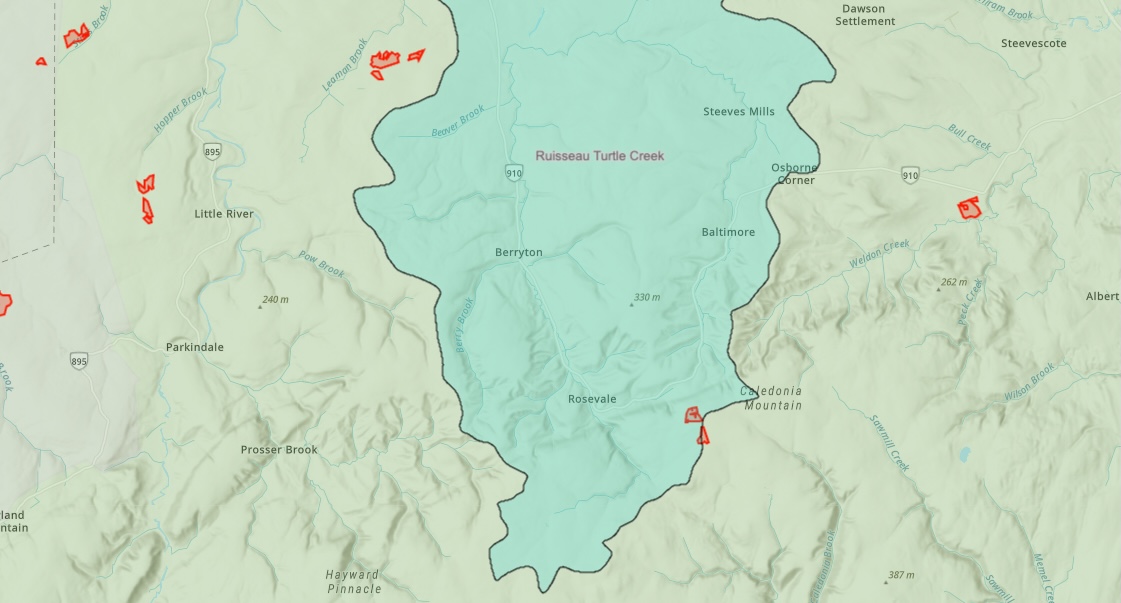

Both maps also show the locations of protected watersheds that provide approximately 300,000 New Brunswickers with their drinking water.

Some pesticide use allowed in protected watersheds

Regulations under the provincial Clean Water Act outline the activities permitted in designated watersheds. Under the regulations, protected watersheds are broken down into three zones: the watercourse itself, a 75-metre “setback zone” on its banks, and the larger area.

Some application of pesticide — an umbrella term that includes herbicide — is allowed within the buffer zone and larger area. Stop Spraying NB wants that practice to end, including on private lands that fall within protected watersheds.

Calculations by Stop Spraying NB indicate that the province issued permits last year that allowed for spraying on 55 hectares within the protected watersheds.

That includes some blocks of land on the southeast edge of the Turtle Creek watershed, which supplies Greater Moncton with its drinking water supply.

The maps show no sign of herbicide use within the protected Ogden Mill Brook Watershed, located near the Trans-Canada Highway and Walker Road.

Sackville’s drinking water supply comes from three drilled wells in that area, according to Jon Eppell, Director of Engineering and Public Works for Tantramar.

However, herbicide spraying licenses were issued last year for numerous blocks of privately-held land north of the Trans-Canada Highway.

The closest block is a 2.5–hectare parcel located about five kilometres north of the watershed. The province gave J.D. Irving Limited permission to spray that land, along with multiple blocks around Big Lake and the Memramcook River, roughly 10-15 kilometres north of the protected watershed.

Pressure ahead of byelections

The environmental group has launched the maps ahead of three provincial byelections scheduled for April 24 in the ridings of Restigouche-Chaleur, Dieppe, and Bathurst East-Nepisiguit-Saint-Isidore. The group wants to make spraying an issue in those races.

Spraying of the herbicide glyphosate is a controversial topic characterized by competing claims and counterclaims from environmental groups, industry, government bodies and scientists about the safety of the chemical.

The widespread use of glyphosate in New Brunswick’s forestry industry has been under renewed scrutiny, particularly in connection with the so-called “neurological syndrome of unknown cause.” A provincial government study last year concluded that the syndrome doesn’t exist, but the story has continued to pester the provincial government.

Last week, a spokesperson for a group of affected patients said people suffering from “atypical neurological decline” in New Brunswick have tested positive for “multiple environmental toxins, including glyphosate,” and the provincial Green Party has called for a renewed investigation.

Stop Spraying NB supports calls for an investigation into possible environmental causes of the syndrome, according to Lubbe-D’Arcy. “We are not claiming that glyphosate has anything to do with it… we just need to have it investigated properly,” she said.