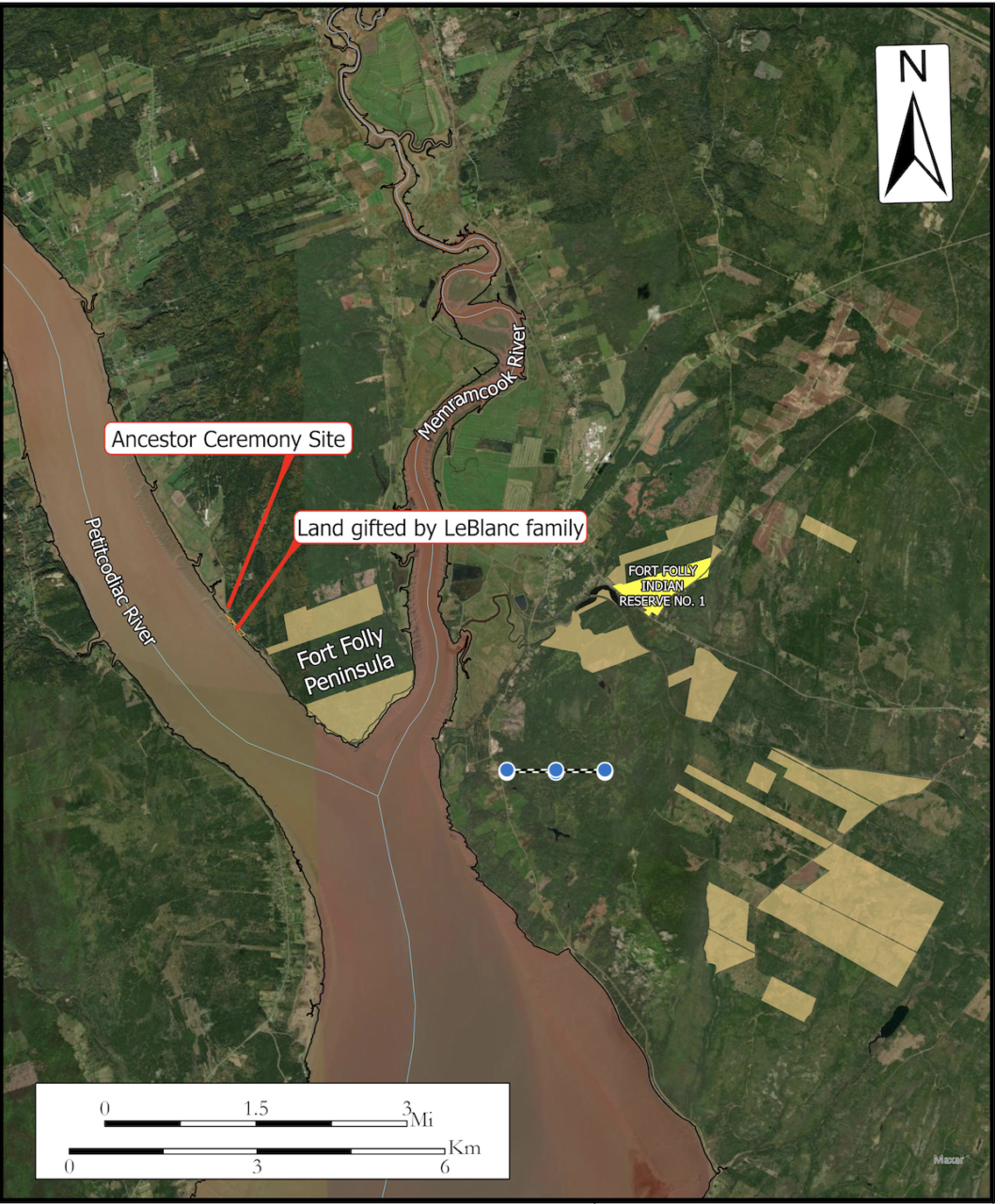

Amlamgog (also known as Fort Folly) First Nation has just announced another parcel of land to be protected under their Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCA) project. The small, three acre strip of land along the Petitcodiac river was given to Amlamgog First Nation by a Memramcook family, after an annual ancestor ceremony held nearby at Beaumont. The latest parcel is part of a growing collection of land protected by the first nation.

Amlamgog cultural coordinator Nicole Porter says the band’s IPCA project is acquiring land through donations and purchases from a fund setup for that purpose. “We hold it in trust for everyone to be able to use in a good way, in a sustainable way,” says Porter. “It won’t be harvested or clear cut. It won’t be developed or anything like that. It is strictly for conservation.”

Three other groups in the province also have IPCA projects underway, and Porter says they work in concert to protect land, and make it open, “to the Mi’gmaq people all across Mi’gmaqi.”

Porter says Amlamgog has identified lands to focus on, including in the Tantramar area, as sacred or useful for gatherings and ceremonial purposes. Part of the plan with the IPCA projects is for the province to match or donate Crown land identified for conservation, but Porter says that hasn’t quite come to fruition. “They haven’t given any of that land, to my knowledge, back,” says Porter.

Amlamgog First Nation has acquired number of parcels of land on the Fort Folly Peninsula (between the Memramcook and Petitcodiac rivers), and also surrounding their current community near Dorchester. Porter says that existing buildings and trails on the land will remain, but the intention is to prevent further expansion or development. For example, the Fort Folly peninsula is home to a number of ATV trails, “and those will continue to be used,” says Porter. “What we would do is just monitor and make sure there’s no additional trails being built.”

Training future land guardians

Porter says part of the project is building a guardianship program, training people in monitoring and conservation, and empowering them to stand up for Indigenous land rights. Currently a group of summer students are being trained in identifying plants, doing water analysis, tracking fish populations and other data collection. They are also looking for dump sites, and working towards cleaning them up along with Fort Folly Habitat Recovery staff.

Porter says that she and colleague Michelle Knockwood will soon go out to the newly gifted land near Beaumont to survey it for plant and animal habitat. The three-acre strip is mostly marsh, but very significant for Amlamgog for its proximity to a sacred burial site, and the original site of the Fort Folly settlement at Beaumont.

“We want to make sure that we continue to honour our ancestors in a good way,” says Porter. The land gift from Daniel LeBlanc and his family came after an ancestor ceremony last week with elder Donna Augustine. The site is home to marked and unmarked graves of previous generations of Mi’gmaq, and Porter says that years ago, Augustine and the late chief Gilbert Sewell had helped repatriate some ancestral Mi’gmaq remains found on Skull Island in Shediac Bay. “It is a very special site,” says Porter.

Traditional gathering and stopping place

Beaumont was once a major gathering place for people from all over Mi’gma’gi, says Porter, with Ste Anne’s Day celebrations often drawing leaders from PEI, Cape Breton, the Gaspé and Newfoundland. The Ste-Anne-de-Beaumont church still stands there, though Porter says Amlamgog no longer uses it for ceremonies.

“But before that church was even built, some of our elders talk about a time where they would just come, and it’d be like a stopping ground or resting spot before they would take off on their journeys,” says Porter. Starting near Beaumont, the tidal bore along the Petitcodiac could take people 20 or more kilometres up river to the Sussex area, says Porter. And from there, people would branch out north and south heading to Quebec and Maine.

Porter says the last three Mi’gmaq families left Beaumont in the 1950’s, and the current Fort Folly First Nation land near Dorchester was officially designated by the federal government in the 1960’s.

‘Allies’ in conservation

Porter says it’s amazing to have “allies coming out and supporting us and donating this land back to conservation.” The LeBlanc family had previously sold some parcels of land on the Fort Folly peninsula to Amlamgog, making a cash donation to the IPCA project at the same time. Other land donated by the Spence family is on its way to becoming a healing forest, with plants from an EOS Eco Energy food forest project.

“As Mi’gmaq people, you know, our pharmacy is right outside,” says Porter. “Everything that we ever needed for thousands of years was right there. So we’re trying to bring that knowledge back, especially for our children here in the community.

“To be able to go out there into that healing forest, to that land, and see there’s my medicine, I can harvest that and use it as a tea or make it into a salve and rub it on my skin… It’s things like that, bringing our culture and getting us reconnected to that land again, is what I see as amazing.”