Today is election day in New Brunswick, and Sackvillians who haven’t already voted are heading to the Tantramar Civic Centre to cast their votes for local representation on the regional health boards, district education councils, and town hall.

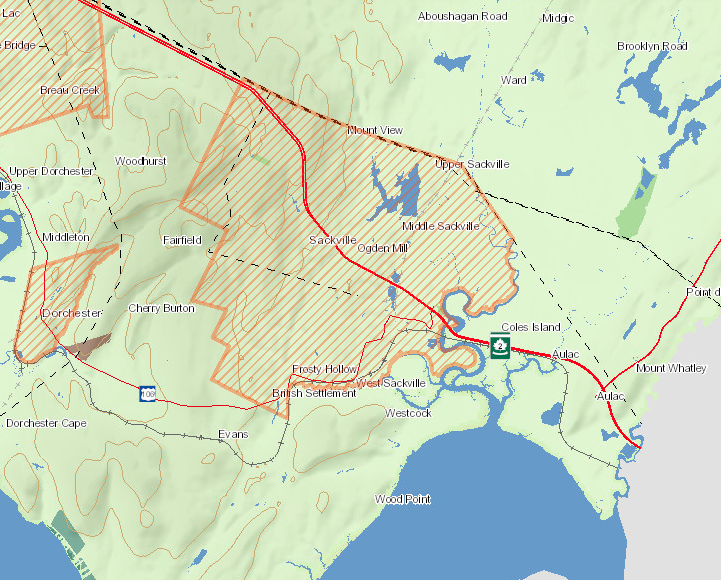

But many area residents will have a decidedly smaller ballot than others. People who live outside of Sackville town limits, in the Sackville parish local service district, won’t be voting for local government representatives on May 10, because they don’t have any.

According the department of local government approximately 30 per cent of the population of New Brunswick lives in local service districts. While some have elected advisory committees, these committees don’t have legislated authority. Department of Local Government and Local Governance Reform spokesperson Anne Mooers says there are currently 164 Local Service Districts with a committee, leaving 85 without. Mooers says the number of LSDs with committees has increased since 2010 when the government created Regional Service Commissions.

CHMA spoke with Mount Allison Professor Geoff Martin to find out about the history behind this lack of local representation for 30% of New Brunswick’s population, and many of Sackville’s neighbours.

A “STRANGE SYSTEM”

Martin agrees it’s a strange system, rooted in New Brunswick’s unique history. And it wasn’t always like it is now.

“If you go back to the 1920s an 30s, municipal government in New Brunswick, like in many parts of the country, was actually the dominant level of government,” says Martin.

Back then, services under jurisdiction of the province were actually mostly implemented by local systems, says Martin. Things like property and civil rights, social services, education, transportation, administration of justice, and “what little they did on health care,” were all turned over to municipal and county governments, says Martin.

“All of New Brunswick was covered by elected, local government,” says Martin. The province has 15 county governments, as well as towns and cities with their own elected councils.

Those municipalities did a lot, says Martin, though they did it “in the style of the 1920s and 30s,” when a county poorhouse was the norm for delivering what we now call social services.

Interestingly, Martin says the municipalities of the time actually had the ability to tax based on income and wealth, which they no longer do, instead relying solely on property taxes as a source of revenue.

AND THEN ALONG CAME LOUIS ROBICHAUD

In the 50’s and 60’s this system started to be seen as inadequate, says Martin, and major change came with the Louis Robichaud government of the 1960s, who started an ambitious Equal Opportunity Program.

“They decided there were serious flaws to this old system of municipal government,” says Martin. “One of them was the great inequality in the provision of public services.”

“The affluent municipalities and counties in southern New Brunswick could afford much better public services than the poorer rural counties, particularly in the Francophone areas in northern New Brunswick,” says Martin. “So you’d have a better education system, better transportation system… better public services in general where there was more money, because the orientation was a very decentralized system.”

Equal Opportunity took aim at these regional inequities with the province taking over and centralizing health, welfare, education and justice. At the same time, the Equal Opportunity Program abolished county governments, and encouraged the creation of city and town governments.

“It was really transformative period,” says Martin.

The idea behind the dismantling of county governments, says Martin, was based on predictions of where things were headed. “They had this sort of modernization theory that said that rural New Brunswick will become depopulated,” says Martin, “and they won’t really need democratically-elected self government.”

And where there were rural population centres, the idea was to create villages and towns with their own councils. The town of Riverview was one such creation, based on a population centre in Albert County. “There were dozens of villages and towns that were created in as a result of Equal Opportunity,” says Martin, “to give democratic self government to those areas of rural counties that actually had significant population levels.”

“They thought everyone else would move into the cities and towns and villages, and they didn’t need to worry about the rural areas,” says Martin. “That did not come to pass, and that’s what’s left us in our current situation.”

LOWER TAXES AND LESS ACCESS TO “SELF-PROTECTION”

“You have all kinds of issues,” says Martin, like what’s called ribbon development, where to avoid municipal taxes, people move just outside of municipal boundaries.” But in addition to lower taxes, local service districts have no representation. “It’s very much laissez faire and much weaker regime in terms of regulation in these local service districts,” says Martin.

“So, the people who are living out there, on the one hand, they pay lower taxes than they would if they were in a municipality,” says Martin. On the other, “they receive far fewer services, and in a way, they have less of what you could call self-protection, or the capacity for self protection.”

By way of example, Martin cites the Metz hog farm that operated in Ste-Marie-de-Kent for six years before shutting down in 2005. Community groups fought against the farm for years.

“It was very hard for the residents who were unhappy to do anything about it, because they didn’t have municipal power,” says Martin. “Nothing that Metz hog farm was doing, in terms of effluent and odour and noise and all this kind of thing, nothing they were doing was really in violation of provincial rules. So the people that were kind of left high and dry.”

The story may sound familiar to some residents in the British Settlement area, who have been complaining of issues with blasting at local quarries for years, but have not been able to get help from the provincial government. In December 2018, an advisory committee formed in an attempt to get actions on issues related to flooding, emergency services, and the effects of blasting in the area. But in January of this year, the five local leaders elected to the Sackville parish LSD advisory committee resigned en masse in protest of a lack of support from government.

LOCAL GOVERNANCE REFORM CONSULTATIONS NEXT WEEK

New Brunswick’s entire system of local government is up for major changes, as the provincial government considers local governance reform. The province has issued a green paper outlining some of the options for reform, including amalgamating areas into larger municipal units.

Public engagement sessions on the topic will happen next week. Two French and two English sessions will be held, one focussing on structure and finance, and the other on regional collaboration and land use planning.

The meetings will be virtual, and people are being asked to register in advance, and also complete a survey online. The deadline for public input is May 31.

Monday, May 17, public session, structure and finance (French) 6:30-8:30 p.m.

Tuesday, May 18, public session, structure and finance (English) 6:30-8:30 p.m.

Wednesday, May 19, public session, regional collaboration and land-use planning (French) 6:30-8:30 p.m.

Thursday, May 20, public session, regional collaboration and land-use planning (English) 6:30-8:30 p.m.