The latest stats are in from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), and the rental housing economy in New Brunswick continues to get worse for those renting. Average rents in the province were up 10.5% in October over the previous year, and the vacancy rate is down from 1.9% to just 1.5% according to the CMHC. At the same time, the price of buying a home in Tantramar is up over 86% since 2019, according to MLS data from local realtor Jamie Smith.

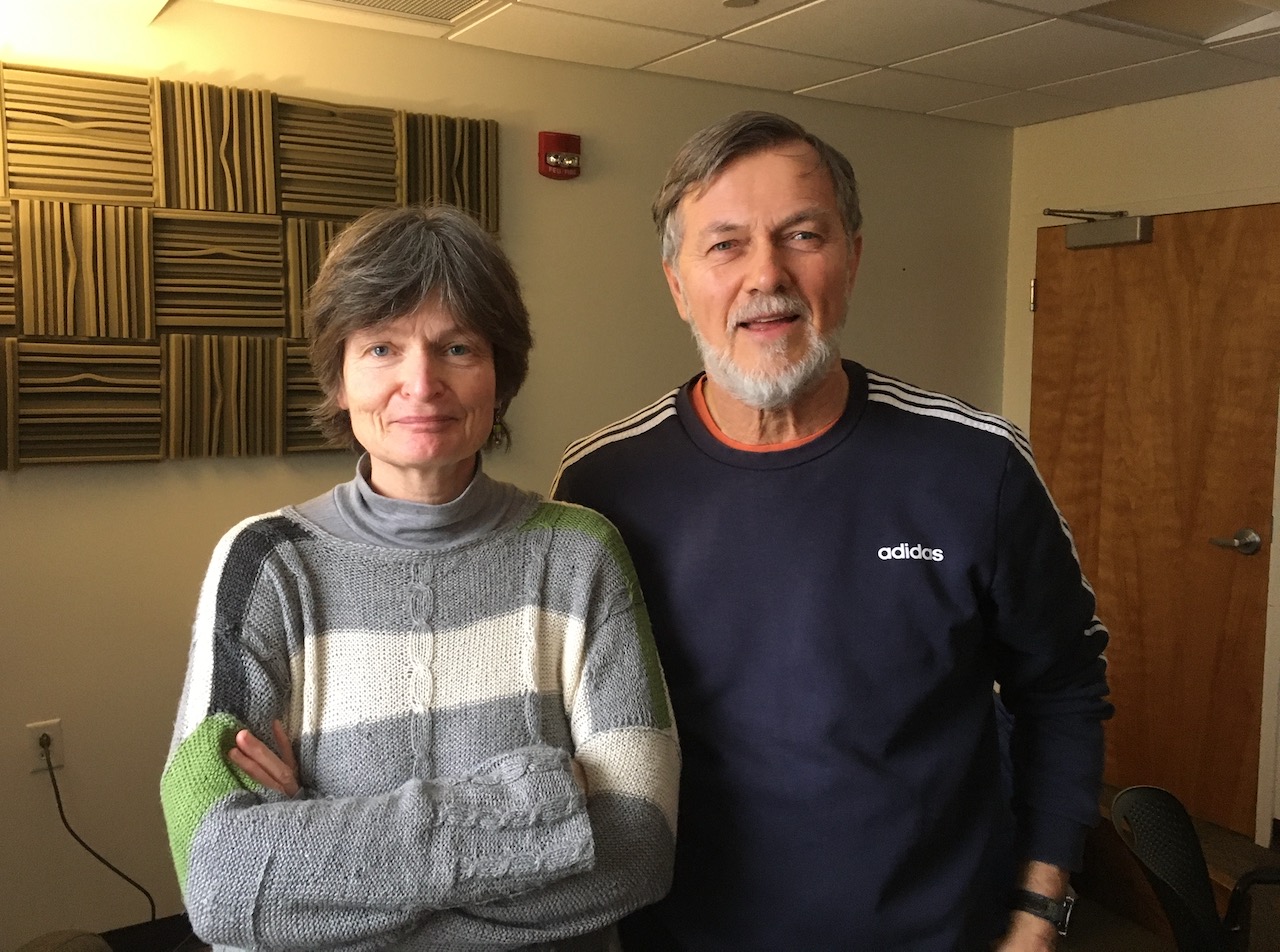

It’s a situation that makes finding affordable housing challenging, and one that Sabine Dietz and Eric Tusz-King have decided they can do something about.

Last week, Dietz and Tusz-King, and the rest of the members of the newly incorporated Freshwinds Eco-Village Housing Co-operative, announced plans for a major new village-style development in Sackville that could provide co-op housing for up to 60 households. Freshwinds has made the first step, purchasing 21 acres of land on Fairfield Road, the former farm of Bill and Inez Estabrooks, for $450,000.

“In order to afford this land, we are selling that house that’s at 64 Fairfield,” says Tusz-King, “and then we’re going to be selling some of the lots along the road.” The Freshwinds development will take place on the acreage behind the roadside lots, and if all goes well, Tusz-King says work on the property could start as early as this fall, with construction starting in spring 2025.

‘The speculation is gone’

Freshwinds is a housing co-operative, meaning that the land on Fairfield and the planned development there is collectively owned by the co-op, and democratically managed by co-op members. “Each member.regardless of how much money they have invested in the cooperative, or the housing itself, has one vote,” says Tusz-King.

Although members share ownership, they can’t sell off their stake in the co-op on the open market. “That’s one of the key characteristics,” says Tusz-King. “One of the problems that we have in Canada with housing is that the value of the land is escalating, and driving up the cost of housing. And that’s all profit for someone.”

“In a housing cooperative,” says Tusz-King, “there’s none of that. The speculation is gone.”

Of course, Freshwinds is making its start in the current economy, and so faces the same high costs as any other development. That means that for about three quarters of the new members, housing costs when they move in will be at market levels. But those prices will not be subject to future market-driven price spikes, providing stability and security in the long term. That’s the main reason that housing fees in Sackville’s other, decades-old housing coop, Marshwinds, seem so affordable by today’s standards.

And like Marshwinds, Freshwinds will also be offering rent-geared-to-income for some of its members.

“There’s a desperate need [for housing] at all economic levels,” says Tusz-King. “There’s a place for market rate rent… but lower income [needs] cannot be met by the private sector. And we know that there’s lots of people in the lower level income, right up to the middle income, that need housing. And so that’s the gap that we’re going to be filling.”

Diverse membership

Right now Freshwinds is made up of just ten founding members who have been working together for the past year on the project. But eventually that will change, says Tusz-King, as the business plan for the property shapes up, and some public funding is secured.

Right now members “range in age and gender identity, language, and that is very intentional,” says Tusz-King, “because we want to be a diverse community.” He says he’d like to see the membership include people from young families to seniors, with a variety of needs and abilities, and a range of incomes represented. He’s also hoping for some new Canadians to figure into the mix.

Dietz says the diverse membership will directly influence what the development looks like. The village will likely include a two-story apartment building as well as townhouses, and the idea is to also include design and amenities that are customized to members.

“The intention is to offer more than just housing,” says Dietz. That could range from landscaping to accommodate gardening, or spaces for music and art. “Even now in the development we’re really talking through how can we incorporate these different lifestyles and ways of living,” says Dietz.

Freshwinds will also be making a commitment in terms of ecological footprint, aiming for a net-zero energy goal for the development once constructed. That will mean “very energy efficient housing” says Tusz-King, as well as possible use of solar panels and district geothermal heating. “We’re also looking at more innovative things like car-sharing, and using electric bicycles,” says Tusz-King.

Public investment needed

Access to public funding will be key to having the co-op get off the ground. While some members have contributed funds, there’s no set buy-in amount for membership. The concept of fairness at Freshwinds is not based on equal financial contributions, but rather on a sense of equity between members, accounting for differing levels of financial wealth. “If people think it’s fair for everybody to pay equally the same amount of money… that’s not the right principle here,” says Dietz. “That’s not how this works in reality, when you really implement the equity question.”

All members do contribute to the work of the co-op, and Tusz-King says the current team has been meeting weekly in order to get as far as they have. Recently, the group hired George Cormier, the former head of the New Brunswick Non-Profit Housing Association who now works with Rising Tide in Moncton, to help navigate the system to raise public investment.

“When we started this a year ago, I said there’s tons of funding out there,” says Dietz. “Once we started digging [into] how to get access to that funding… It’s a nightmare.” Dietz says the process is “disorganized to the hilt,” and profoundly disappointing. “I can’t imagine how we want to have good housing in this province without having really good and solid coordination and support,” she says.

In addition to the business plan and funding, there’s plans to be drawn up for the eco-village, involving architects and engineers, and planning out the construction team, which might be put together with different contractors taking on different components of the village. It’s all something Tusz-King says will be tackled in the next seven or eight months.

‘We’re doing something really big, here’

While the current plan is aiming for up to 60 units of varying sizes in the development, Tusz-King hopes that in the long term they could build even more. “21 acres is a lot of land,” he says.

The scale of the proposed Freshwinds project is much larger than its local counterpart, the Marshwins, but there are other models elsewhere of similar size. Dietz says the group has support from other co-ops and co-op associations, sharing their experience about what’s worked and what hasn’t.

While she admits to getting the jitters about the scale of what Freshwinds is taking on, she’s also excited at the prospect.

“We’re doing something really big here,” she says. “And just setting that scariness aside… We know it’s needed. We know we can do it. We just need to line it up properly. And I think it’ll work. It’ll work well.”