Hear this story as reported on Tantramar Report:

Allegations of sexual misconduct dating back to 2018 at Mount Allison University have come up again on social media, and while a prominent campus activist says the university has a duty to investigate, Mount Allison says doing so would be “impossible.”

Mount Allison graduating student and activist Michelle Roy kickstarted a massive protest last November, demanding the university review and change its policies and procedures around sexual violence on campus. That process is now underway, with an independent consultant hired to review and make recommendations on Mount Allison’s policies, and Roy serving as co-chair of a Sexual Violence Prevention Working Group.

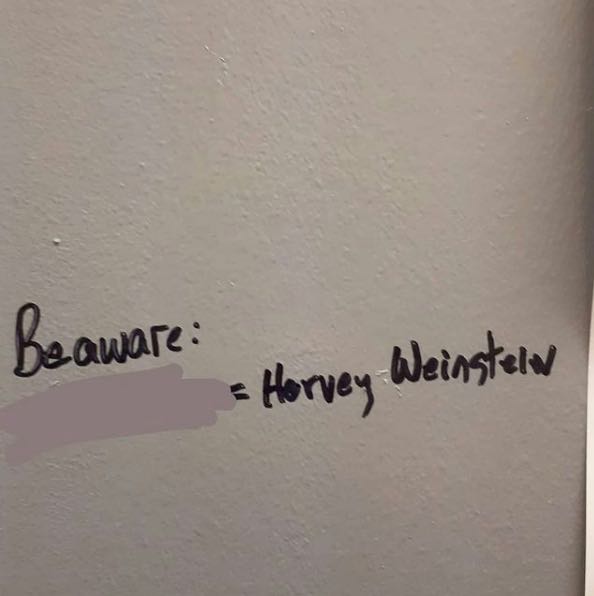

Roy recalls when the anonymous allegation first appeared as graffiti on a bathroom stall–and then proliferated on social media–back in August and September 2018. The graffiti equated someone at Mount Allison to Harvey Weinstein, the then-accused and now-convicted rapist.

The event sparked Roy’s activism around sexual violence. She says the repeated appearance of graffiti on Mount Allison walls, even after being erased or covered over, worried her. “For me, it was clearly a cry for help,” says Roy. “A cry for the university to do something.”

At the time, Roy met with the university’s sexual violence prevention advisor and pushed for action. “I really, really wanted the university to investigate,” says Roy, “and they refused to.”

Mount Allison University has confirmed that they indeed did not investigate the anonymous allegation from 2018. Rob Hiscock, Mount Allison’s director of marketing and communications, responded via email to say that it would be “impossible” to have done so.

“No disclosure of misconduct or formal complaint was reported related to the graffiti that was found on campus in 2018,” writes Hiscock. “By definition, anonymous and unattributed claims are impossible for the University to investigate.”

Roy says the lack of action by the university in absence of a formal complaint is problematic. “That for me was one of my first experiences where I realized that the policy wasn’t working on campus,” says Roy. “That Mount Allison was able to report low numbers of sexual violence because nobody wanted to come forward, as they would have to formally put their names [down].”

Making a formal report, especially against someone of higher authority, is scary, says Roy. “Sometimes it’s terrifying,” she says. “And it’s a personal choice.”

But regardless of the formality of the complaint, Roy still thinks the university has a duty to investigate, “especially if it’s someone of authority on their campus.”

“I understand that charges can’t be laid,” says Roy. “But I think there needs to be a certain process where it’s acknowledged, and in a way, it’s somewhat investigated. Again, especially if it’s someone of authority that is paid by Mount Allison. There needs to be an HR process.”

CHMA has had no contact with the person who created the anonymous graffiti or the person who posted it on social media, and for legal reasons cannot provide further information about the anonymous allegation.

UNIVERSITY POLICY “ENCOURAGES THAT NOTHING BE DONE”

Roy says she doesn’t believe Mount Allison’s policies prevent them from looking into an allegation such as the repeated graffiti from 2018, but she says the policy “encourages that nothing be done.”

In the end, says Roy, the policy is “not there to protect people. I think it’s there to protect themselves, so they don’t have to go through the process. Because if they decide to investigate a certain person, there’s a lot of legality, there’s unions, there’s different things involved, and it just gets complicated.”

Roy holds out hope that the independent review of Mount Allison policies and procedures on sexual violence will take into account situations such as the anonymous allegation.

The Canadian Centre for Legal Innovation in Sexual Assault Response (CCLISAR) is the group hired to review current policies, consult the university community, and report back in June with recommendations. Roy says the consultants at CCLISAR have been made aware of the course of events surrounding the 2018 allegation.

THE CHOICE TO REPORT IS PERSONAL, SAYS ROY

Roy herself has chosen to report sexual assault in the past, choosing to tell her story publicly last November. But ultimately it’s a personal choice, she says, and there are reasons for people to chose either path.

“For a lot of people, I think it’s hard to understand why someone wouldn’t want to report,” says Roy. “But there needs to be a deep understanding that it’s not one person’s responsibility to protect other people.”

Reporting comes with potential for more trauma, says Roy, especially when it results in no action or consequences. It’s also time consuming, and comes with risk of retaliation.

“People really fear retaliation,” says Roy, “and there’s not much done on campus to protect you against retaliation. I’ve known people who have suffered retaliation because they have decided to formally report, and it’s just a terrifying and traumatizing experience that really stays with you and gives you a whole new sense of fear.”

There are also pros to reporting, says Roy. “It’s liberating for some people to be able to tell their stories and formally put it down.” While there is a risk that no action will be taken, there is also the chance that it will. An investigation, and consequences applied as a result, can feel like justice. “Honestly,” says Roy, “even just the investigation process sometimes is enough to scare people into acknowledging what they’ve done and reflecting on their actions.”

But Roy is careful to stress that she doesn’t mean it’s always the right thing to do. “It’s your own personal choice, and there should never be pressure,” she says.

Roy advises anyone considering reporting to contact Crossroads for Women, also known as the South East Sexual Assault Centre.

“They have an outreach officer, Melissa, and she’s here in Sackville,” says Roy. “She’s able to do phone calls, texting, emails, in person meetings. She is the best advocate because she she works closely with the university right now… but she is completely independent from the university. So she has your intentions in mind,” says Roy.

Crossroads has a free 24 hour crisis line, 1-844-853-0811, and outreach worker Melissa Godin-Belliveau is available a 506-381-8808 or melissab@crossroadsforwomen.ca.