Hobby photographer Shawn Chapman spends a lot of time with his camera pointed at the night sky, in hopes of capturing the aurora borealis, or the northern lights. The Amherst area resident has been chasing the aurora borealis with his camera for about six years, sometimes heading out on 15 minutes notice to spend hours in wait.

Recently, his dedication paid off. In the early morning hours of November 4, after having already spent the previous night capturing images, Chapman got word that the aurora would be a more active that morning. “So I told my wife, I’m going,” says Chapman.

He grabbed his gear and went off to his spot, about 5-7 minutes outside Amherst, overlooking the Tantramar marsh. He knew when he got there he’d be in for something good. “I couldn’t see the colours,” says Chapman, “but I could see the light bands and stuff moving through the dark sky.” Chapman set up his camera, using a short focal length lens, tripod, and time lapse setting.

As the first images came through, he realized just how lucky he was. “It’s the best I have ever experienced in five to seven years,” says Chapman. You can view more of Chapmans’s photographs here.

The images show bands of vibrant green, red, pink and violet glowing along the horizon and up into the night sky. Though the colours aren’t visible to the human eye, a camera with the right settings can pick up the frequencies.

“Our human eyes are just not as sensitive as the digital device inside the camera that’s recording the light,” says astronomer Dr. Catherine Lovekin. “We see the same thing with astronomical images.” And long exposure times also help. “If you have a long exposure, you collect more light. And so you can see the colours that are normally too faint to be seen with just your eyes.”

Lovekin is an associate professor and head of the physics department at Mount Allison University. She says displays of the Northern Lights as far south as the Tantramar Region are “not super common, but it does happen from time to time. This is, I think, the second or third time in the eight years I’ve been in Sackville that we’ve been able to see them this far south.”

Chapman says he usually gets just 15-20 minutes notice of aurora activity on the apps and websites he checks. The solar storms which ramp up the amount of charged particles streaming off the sun, causing the aurora to be more visible farther south, are very unpredictable, says Lovekin. “There’s no way you can forecast them the way we can the weather. We can predict that the sun gets more active, and so that we’re more likely to see solar storms over the next few years, but we can’t predict there’s going to be one. It’s a very sudden event. It just happens and you have to be ready for it.”

Lovekin says in the current solar cycle, the sun’s activity is just starting to ramp up and is expected to peak in 2025 or 2026. “We can expect to see more storms over the next few years,” she says. “To view them all you need is a clear view of the Northern horizon and a nice dark sky.”

Chapman says he’ll continue on the aurora beat in the years to come, but doubts he’ll get shots as remarkable as those he took on November 4, 2021. “I’ll never retire from it,” he says. “It doesn’t matter how many times I photograph them.”

What’s going on when we see the Northern Lights?

Here’s Dr. Catherine Lovekin, answering this rather big question on Tantramar Report:

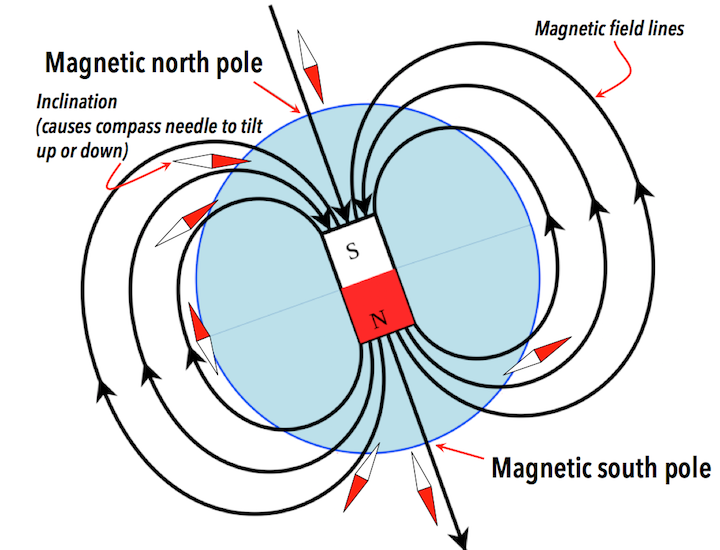

“It’s a pretty complicated process. So I mentioned these solar storms. They all start with the sun. The sun has what we call the solar wind, which is just charged particles, things like electrons and protons, hydrogen atoms that have lost their electrons, so they have the charge. And they’re streaming off the sun all the time. But then there are these events, solar storms, where they get more of them. And so those charged particles stream out through space, and eventually they encounter Earth’s magnetic field. And Earth’s magnetic field is a dipole magnetic field, so the same kind of magnetic field as you have with a bar magnet. You’ve got the North Pole, and then magnetic field lines coming out and making sort of big half circles and going back into the South Pole.”

“And when the charged particles encounter our magnetic field, they get caught. And they get funneled in along those field lines towards the poles. So they can’t reach the Earth’s surface at the equator because of these magnetic fields. And that’s good for us because these particles are very high energy and they’d be very damaging to our bodies, if they could actually reach the surface and hit us. It’s kind of like ultraviolet radiation, the same idea. They just got a lot of energy and they can damage your DNA. But they do get funneled in, they have to follow the magnetic field, and so they go in along the poles.

“And so normally aurora show up near the poles where these charged particles then start to interact with the particles in our atmosphere. Because they have so much energy, they strip the electrons off things like oxygen in the atmosphere, and then when the electrons recombine, get back together with the oxygen atoms, they release light. And that’s what we see as the Aurora.

“So in normal times that happens near the pole. But during a solar storm, there’s so many of these electrons coming from the sun that the magnetic field kind of gets overwhelmed. And so they get funneled in at the pole, but also closer down towards the equator. And the stronger the storm, the farther south they’re visible.”